|

English Publications

Research

Papers

CODE-SELECTION IN CHINESE/ENGLISH BILINGUAL COMMUNICATION

INTRODUCTION

In a society where many members can speak more than one language,

communication in which two or more languages are alternatively used

is a common phenomenon. This language situation has been the subject

of considerable research in the past few decades, and studies using

different approaches have revealed various kinds of factors affecting

language alternation in bilingual communication, including linguistic

factors (Gumperz 1982; Pfaff 1976; Poplack 1980; Sankoffand Poplack

1981; Woolford 1983; etc.), sociological factors (Blom and Gumperz

1972; Ferguson 1959; Fishman 1972 1978; Fishman, Cooper and Ma 197

1; Scotten 1983; Scotten and Ury 1977; etc.), sociocultural factors

(Blom and Gumperz 1972; Ervin-Tripp 1964; Giles 1979; Zentella 1981;

etc.), pragmatic factors (Auer 1984 1988; Gumperz: 1982; Scotten 1988;

Vald6s 198 1; etc.), and environmental and psychological factors (Bentahila

1983; Brown and Fraser 1979; Pyrne1969; Genesee and Bourhis 1981;

Giles 1979; Lambert 1967;,Ryan and Giles 1982;.etc.). Although these

studies have made significant achievements, language alternation is

still a subject of much debate among researchers.

As a departure from the above work, this study takes a communication

approach that treats language alternation basically as a communication

phenomenon, functioning to establish relationships and transmit messages.

It uses a relational system to analyze Chinese/English bilingual communication

and provides its general modes of codeselection. It deals with code-selection

only in the initial conversation and not with code-shifting or code-switching

during the conversation.

DATA AND RESULTS

Data were collected during the one-year fieldwork (May 1991 - May

1992) in and out of Chinese communities in New York City, in which

lived a Chinese population of "about 30,000, with halfofthem

Bring in Chinatowns" (Xia 1992:202). They speak a variety of

Chinese dialects, I such as Mandarin, Cantonese, Min-nan, Wu, etc.

Although the exact number of the people of each dialect is unknown,

it is estimated that "71.5% of Chinese Americans speak Mandarin,

5% speak Cantonese, 4% speak Min-nan. Although many people speak other

dialects than Mandarin at home, most of them can speak Mandarin"

(World Journal May 15th 1992: 20). In Chinatown, Cantonese and Min-nan

are the dominant dialects. In other Chinese communities, Mandarin

is dominant over other dialects.

897 conversations were recorded by observation of and personal participation

in daily natural social interaction in a variety of societal domains,

including communication in the streets, stores, schools, offices,

public services, companies, parties, and homes, between strangers,

friends, colleagues and fellow workers, students and teachers, doctors

and patients, servicemen and customers, family members, etc. These

conversations ranged from the shortest consisting of only a few words

to the longest made of dozens of utterances.

Of the 897 conversations, there were 394 initial selections of English

and 503 initial selections of Chinese, which demonstrates a high frequency

in language alternation. The data show that these codeselections were

made in a close relation with the relationships of the communicators.

Table I describes this relation. It shows that English was selected

more frequently between non-intimates than Chinese, which was more

often used between intimates, and that the more intimate the relationships

were, the more frequently Chinese was selected.

METHODOLOGY: AN ANALYTIC SYSTEM OF RELATIONSHIP

There are certainly many ways to view the possible relationships that

can bring people into communicative interaction, and the nature of

these relationships can be defined within a variety of different perspecfives

and hence within a different system of interaction categories. As

some aspects of information processing are unique to bilingual communication,

I will, for my analytic purpose, define relationship in terms of three

dimensions: (1) ethnic backgrounds, (2) levels of intimacy, and (3)

roles. Each of these dimensions contains a dichotomy of relational

categories. The dimension of ethnic backgrounds has categories of

interethnic and intraethnic relationships; the dimension of levels

of intimacy has categories of intimate and non-intimate relationships;

and the dimension of roles has categories of long-term (L-Term) and

short-term (S-Term) relationships. These three dimensions together

with their six categories form a complete analytic system ofrelationship

(Diagram 1).

Table 1 Relationships and Code-Selections in Chinese/English Bilingual

Communication

| Relationships

|

Total |

English |

% |

Chinese |

% |

| Non-Intimate

Semi-Intiniate

Intimate

|

284

159

454

|

242

63

89

|

85.2

39.6

36.5

|

42

96

365

|

14.8

60.4

80.4

|

| TOTAL |

897 |

394 |

43.9 |

503 |

56.1 |

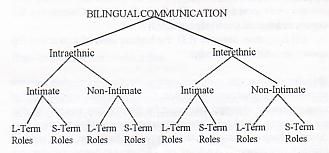

Diagram1. An Analytic System

of Relationship in Bilingual Communication

Diagram l illustrates

a descending order of level among these three dimensions. "Intraethnic"

and "interethnic" are the first level of bilingual communication,

under which different kinds of relationships are categorized: (1)

long-term intimate intraethnic, (2) short-term intimate intraethnic,

(3) long-term non-intimate intraethnic, (4) short-term non-intimate

intraethnic, (5) long-term intimate interethnic, (6) short-term intimate

interethnic, (7) long-term non-intimate interethnic, and (8) short-term

non-intimate interethnic. These kinds of relationships are finally

defined by the roles communicators play in their social interaction.

There are two kinds of roles in bilingual communication: social and

cultural roles. Social roles are those such as father, son, supervisor,

employee, doctor, patient, etc. Cultural or ethnic roles are those

such as Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Hispanic, American, etc. Among

the social roles, some relationships are longer-term and more intimate

than other relationships. For example, a father-son relationship is

longer-term and more intimate than adoctor-patient relationship. For

the cultural/ethnic roles, an intraethnic relationship is generally

more intimate than an interethnic relationship. The structural relations

among the three dimensions of relationship in bilingual communication

is, in this way, best represented by the interrelationship between

levels of intimacy and the other two dimensions, represented by the

two kinds of role-relationships respectively: the social and cultural/ethnic

role-relationships.

Four levels of relationships are formed, based upon frequency of interaction

and levels of mutual knowledge.

(a) short-term non-intimate (SN): the lowest level of interactive

frequency and mutual knowledge;

(b) long-term non-intimate (LN): the lower level of interactive frequency

and mutual knowledge;

(c) short-term intimate (Sl): the higher level of interactive frequency

and mutual knowledge; and,

(d) long-term intimate (Ll): the highest level of interactive frequency

and mutual knowledge.

SN refers to a one-time-or-never communication relationship between

people with no prior communication. Communicators with this kind of

relationship are strangers, who meet for the first time and may or

may not meet again. This kind of communication usually takes place

in public domains, such as asking directions, shopping, first visits

to doctors and lawyers, first meetings at parties, etc. LN refers

to occasional communication relationships between people who have

a very short history of communication and know each other, but not

very well. Communication of this kind usually takes place between

people who have lived, studied, or worked together for a very short

period of time, or between people who have met several times at stores,

parties, doctors' and lawyers' offices, etc. SI refers to frequent

communication relationships between people who have a long history

of communication. Communication of this kind is usually found among

people who have lived, studied, or worked together for a rather long

period of time, or had frequent meetings at public services, and know

each other rather well. LI refers to extensive communication relationships

between people who have a very long history of communication and know

each other very well. Communication of this kind takes place among

family members, relatives, very good friends, colleagues of long standing,

etc.

lf we group (b) and (c) into the level of serni-intimacy, we get three

levels of intimacy on the following relationship continuum.

Graph 1. The Three Levels ofIntimacy ofthe Relationship Continuum.

Intimate

Semi-intimate

Non-infuriate

(LI)

(SI and LN)

(SN)

These three levels of intimacy represent three developmental stages

of relationship in the process of communication: (1) non-intimacy

is the establishing stage, (2) semi-intimacy is the developing stage,

and (3) intimacy is the developed stage. Relationships develop from

the short-term non-intimate relationship (SN) through the long-term

nonintimate (LN) and the short-term intimate (SI) relationship to

the longterm intimate relationship (LI); or they may change the other

way round.

ANALYSIS

Non-Intimate Communication

The data indicate that English is the most frequently selected in

non-intimate Chinese/English bilingual communication. Two characteristics

of non-intimate communication are important in determining this selection:

(1) there is no prior social interaction between communicators; and

(2) they have a formal relationship.

People who have no prior social interaction and engage in communication

for the first time know (almost) nothing about each other, including

their ethnic backgrounds and language proficiency. This implies that

their communication can be either interethnic or intraethnic, and

that the language used in the communication can be in-group or outgroup.

In such an ambiguous situation, in order to make communicabon possible,

people will select a language which can cover both possibilities,

a language that can be used in both intraethnic and interethnic communications.

In the United States, this language is English, a majority language

used in most social and cultural domains and between people with the

same and different ethnic groups.

People who have an initial social interaction also have, in most cases,

a formal relationship. In an environment where two languages are used,

people will select a language that can better establish this formal

relationship. In a multilingual society, different languages play

different social functions. Ferguson (1959) and later Fishman (1967;

1972) describe a language situation called diglossia, a situation

in which two languages (or two varieties of a language) have very

precise and distinct social functions. One language is learned largely

through formal education and used in formal situations like church

sermons, political speeches, university lectures, and news broadcasts,

and the other language is largely learned through informal channels

and used in informal situations, like instructions to servants, and

conversations with family members, friends and colleagues (see Ferguson

1972: 236). The former language is called H language and the latter,

L language. Situations in which H language is used usually involve

communicators with formal relationships, while situations in which

L language is used usually involve communicators with informal relationships.

In the United States, English as H language is used in most formal

communications, and other minority languages (L languages) are mostly

used in informal communications. Studies of language use in the United

States have shown that English is usually used in bilingual communication

involving non-intimate or less intimate formal relationships, while

other languages are more often used in bilingual communication involving

intimate or more intimateiformal relationships (see, among others,

Ervin-Tripp 1964; Fishman 1966; Flores and Hopper 1975; Haugen 1953;

Lance 1975; McClure 1977). The Chinese/English communication data

have the same results (see Table 1).

As Table 1 shows, Chinese is also used in non-intimate Chinese/ English

bilingual communication. Several reasons were found for this selection.

First, a low language proficiency in English will limit the possibility

to select it in communication. Of the 42 cases in which Chinese was

selected, there were 18 in which communicators had difficulty in using

English in communication. They spoke very little, broken English.

Second, kinds of communities

in which communication takes place will affect code-selection. Table

2 shows that Chinese is used more frequently in the Chinese communities

than in the non-Chinese communities. This is because of the function

of the Chinese communities in defining the ethnic and linguistic contexts

of communication. In the Chinese communities, most communicators are

Chinese and Chinese is the majority language, even though English

is the formal language. There is greater communicability by speaking

Chinese than by speaking English. By using Chinese one will meet less

difficulty in communication in a Chinese community than in a non-Chinese

community.

Table2. Code-Selection in Non-Intimate Chinese Americans' Bilingual

Commufffication

| Locations/Situations |

Total |

Egnlish |

% |

Chinese |

% |

Non-Chinese Communities

formal

informal

|

85

49

|

81

40

|

95.3

81.6

|

4

9

|

4.7

18.4

|

Chinese Communities

formal

informal

|

94

56

|

82

39

|

87.2

69.6

|

12

17

|

12.8

30.4

|

| Total |

284 |

242 |

85.2 |

42 |

14.8 |

Third, informal situations can redefine the formal relationships between

non-intimate communicators and reduce to some degree the formality

in initial social interaction, giving communicators more freedom in

selecting codes. Table 2 indicates that Chinese is used more often

in informal situations than in formal situations. This is because

in informal situations, communicators, though non-intimate, are less

controlled by situations and are thus less restricted by the mode

of code-selection required by non-intimate communication. In brief,

non-intimate communicators are freer in selecting a code in their

own communities and in informal situations than in other groups' communities

and in formal situations.

Fourth, the involvement of an intimate in the communication between

non-intimates can modify the non-intimate relationship between the

latter, leading to their selection of a more intimate code, Chinese.

This phenomenon is found common in introductory communication, in

which the code selected by the introducer often determines the code

selected by the introduced. The reasons for this are that (1) the

code selected by the introducer reveals information about the language

backgrounds of the introduced: it indicates that the introduced can

understand or may speak that code; (2) as the introduced are the intimates

ofthe introducer, they may know something about each other from the

latter; (3) as the communication between the introduced is initiated

by their intimate, the introducer, the mode ofcommunication is not

as formal as that between two complete non-intimates; and (4) as the

introduced are the introducer's intimates, they are psychologically

attached with a little, if not great, intimacy. In this way, the more

intimate code, Chinese, will be selected by the non-intimate introduced.

Semi-Intimate Communication

The two kinds of semi-intimate communicators - long-term nonintimate

(LN) and short-term intimate (Sl) - represent two phases of relational

development with the latter being more intimate than the former, and

as the Chinese/English communication data show (Table 3), their bilingual

communication indicates a general tendency towards an increased use

of the native language in communication.

Communicators in semi-intimate communication are in a stage of developing

relationships from less intimacy to more intimacy. To develop their

relationships, they need to use a language that marks more intimacy

than non-intimacy. As the native language of an ethnic group marks

an ingroup relationship, while the non-native language marks an outgroup

relationship, in ingroup communication the native language will mark

a more intimate relationship than the non-native language. Therefore,

the native language of an ethnic group plays a more important role

in developing relationships in intraethnic communication. By using

the native language in intraethnic communication, members of an ethnic

group can develop a less intimate relationship into a more intimate

one more effectively than by using a non-native language, that marks

a less intimate, intereffinic relationship.

Table3. Code-Selection in Chinese/English Bilingual Communication

between Serni-Intimate Chinese Americans Whose First Language was

Chinese.

| Relations |

Total |

Chinese |

% |

English |

% |

|

IN

SI

|

76

83

|

24

72

|

31.6

86.7

|

52

11

|

68.4

13.3

|

| Total |

159 |

96 |

60.4 |

63 |

39.6 |

The following factors were

found important in developing relationships and increasing the use

of Chinese. First, people who were socially equal would start to use

Chinese earlier than people who were socially unequal. This is because

the more equal the social relationship is, the shorter the social

distance will be, and the more social interaction results. Second,

people would start earlier to use more Chinese as a result of a faster

relational development in informal social interaction- at a party,

afamily gathering, atour, etc.- than in formal social interaction,

such as at a public meeting, lecture, and work. This is because informal

communication leads to more exchange ofpersonal information, speeding

up mutual understanding and knowledge. Finally, people would develop

a more intimate relationship faster with people who had the same geographic

backgrounds and would start to use Chinese earlier with them than

with the people who came from different places. Mainland Chinese have

a greater ease in developing an intimate relationship among themselves

than with Taiwanese. Both Mainland Chinese and Taiwanese have greater

difficulty in developing intimate relationships with Hong Kong Chinese

and American-bom Chinese. This is probably because Mainlanders share

more social and cultural traditions with Taiwanese than with Hong

Kong and American-born Chinese. Among Mainlanders, people from the

same locale would feel closer to each other than to people from different

locales. They would prefer to use local dialects in their communication

because of its more intimate nature.

English, however, was still used rather frequently in semi-intimate

communication, especially in LN communication. This is because semi-intimate

communication is still in a stage of developing relationships. Therefore,

communication, although not primarily, still marks the other "half'

of the semi-intimate relationship, i.e., the semi-non-intimate relationship.

To mark the semi-non-intimate relationship, communicators will select

a code that marks a more non-intimate relationship than an intimate

relationship. As discussed above, the non-native or the outgroup language

usually marks the former relationship and the native or the ingroup

language usually marks the latter relationship. Therefore, while usingthe

native language to develop their relationships, communicators still

use the non-native language to mark their not well-developed semiintimate

relationships, although not morethan that used in non-intimate communication.

Table 3 shows that English is more used in LN communication than in

SI communication. This is because the relationship involved in the

former is less developed and less intimate than that in the latter.

In LN communication, the relationship is rather formal and sometimes

socioculturally unequal, while in SI communication, the relationship

has been developed into a rather informal or socioculturally equal

one. With this development, English is used less and less than Chinese,

as the relationship develops more and more intimate.

Intimate Communication

In intimate communication, as relationships of communicators have

been well developed, communication functions primarily to transmit

messages. Code-selection will be mainly based upon the language proficiency

of communicators to transmit messages more efficiently.

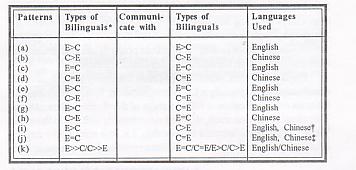

Of the 454 conversations between intimate communicators, eleven patterns

are isolated, that indicate that language proficiency is important

in code-selection (Table 4).

Table

4 Patterns of Code-Selection in Intimate Chinese/English Bilingual

Communication

Notes.

* E=C: almost balanced English-Chinese bilinguals (the order ofthe

languages indicates the order of bilingual proficiency: the first

is the first language and the second, the second language). Bilinguals

of this kind have English as the first language and Chinese as the

second language but can speak and understand Chinese almost as well

as English.

C=E: almost balanced Chinese-English bilinguals. Bilinguals of this

kind can speak and understand English almost as well as Chinese.

I>C: imbalanced English-Chinese bilinguals. Bilinguals of this

kind have some difficulty in speaking or understanding Chinese.

C>E: imbalanced Chinese-English bilinguals. Bilinguals of this

kind have some difficulty in speaking or understanding English.

E>>C: extremely imbalancedEnglish-Chinese bilinguals. Bilinguals

of this kind have great difficulty in both speaking and understanding

Chinese.

C>>E: extremely imbalanced Chinese-English bilinguals. Bilinguals

of this kind have great difficulty in both speaking and understanding

English.

+ E>C bilinguals speak English to C>E bilinguals, who speak

Chinese to the former.

++ E=C bilinguals speak English to C=E bilinguals, who speak Chinese

to the former.

Table 4 shows two general situations in intimate Chinese/English bilingual

communication: (1) if the first language of the communicators is the

same, that language is used (a-f); and (2) if the first languages

of the communicators are different, the mode of code-selection is

rather complicated. There are two possible ways: (a) each of the communicators

uses his/her own first language (i and j); and (b) one of the communicators

accommodates to the language of the other communicator(s) (g and h;

k involves both of the situations). These two possible ways are often

determined by the levels of language proficiency ofcommunicators.

From Pattern (a) through Pattern (d), the speaker and the listener

are identical in their language proficiency. In Patterns (a) and (c),

English is the first language for both the speaker and the listener;

and in Patterns (b) and (c), Chinese is the first language for both

the speaker and the listener. In Patterns (e) and (f), although the

speaker is different from the listener in his/her second language

proficiency, they share the same first language; so they select their

first language in communication. In Patterns (g) and (h), the speaker

and the listener differ in both the first and the second language;

they further differ in their second language proficiency: one is an

imbalanced bilingual and the other is an almost balanced bilingual.

Communication between bilinguals ofthis category will require that

the almost balanced bilingual accommodates to the language ofthe imbalanced

bilingual. Therefore, in (g), the C=E bilingual accommodate to the

E>C bilingual: English is used; and in (h), the situation is just

the other way round. In Patterns (i) and (j), the speaker and the

listener are different from each other in the first and the second

language, butthey share one thing, that is, either they are both imbalanced

bilinguals, or they are both almost balanced bilinguals. Therefore,

in terms oflanguage proficiency, they are equal. In (i), if the E>C

bilingual selects Chinese, the C>E bilingual's first language,

it will be easier for the latte rto decode messages, but it will be

difficult for the former to encode messages. If the E>C bilingual

selects English, it will be easier for him/her to encode messages

but it will be difficult for the C>E bilingual to decode messages.

It is the same with the C>E bilingual. So no matter which language

is selected, there will always be some difficulty for one or the other

of them. In this case, there will be almost no reason for them to

accommodate each other. Each selects his/her own first language, which

is at least faster and more accurate for the speaker to encode messages.

Encoding goes before decoding and the speaker supposes that the listener

can decode the messages. If the former finds that the latter cannot

decode the messages, he/she will, with some difficulty, switch to

the other language, the listener's first language; that is why there

is more frequent code-switching in (i) communication. In Pattern (j),

the reason for communicators to select their first language is almost

the same as that in Pattern (i): no matter which language is selected,

there will always be some difficulty for one of them, owing to the

difference between the first and the second languages. Moreover, since

both the speaker and the listener are almost balanced-bilinguals,

they are more proficient in using the second language in communication:

the listener has less difficulty in decoding messages in his/her second

language, so communication is more successful than communication of

Pattern (i) this is why there is less code-switching in (j) than in

(i). In Pattern (k), as one of the communicators has much difficulty

in his/her second language, s/he and other communicators have to select

his/her first language in communication.

To illustrate these patterns of code-selection, an examination of

communication in the family domain is necessary. Two situations of

code-selection were found in family communication: (1) all family

members use either Chinese or English in their communication; and

(2) some family members use Chinese and some use English in their

communication. For the first case, either Chinese or English is the

first language of all the family members. The situation in which Chinese

is the first language of all the family members and is used as their

medium of communication is found in most newly immigrant Chinese families

or families residing and working in Chinatowns, where daily communication

is conducted with Chinese as the main medium. The situation in which

English is the first language of all the familymembers and is used

as their medium ofcommunication is found mostly in second- or third-generation

Chinese American families, whose members were all born in America,

or in families in which childrenwere either born or raised in America

and in which first-generation Chinese-American parents have received

higher American education or work in places where English is the main

or the only communication medium. All the members of this kind of

family actually have acquired and use English as their first language.

The second case in which some family members use Chinese and some

use English in their communication is found common in families where

Chinese is the first language for some family members, and English,

for the others. The most common situationis as follows: parents are

first-generation Chinese Americans with Chinese as their first language,

and their American-born or American-raised children speak English

as their first language. Communication is conducted between parents

in Chinese, among children in English, and between parents and children

in their first languages respectively: parents speak Chinese to the

children, who respond in English.

This kind of language-crossing phenomenon is found most commonly in

families in which the parents' language proficiency in both Chinese

and English is almost balanced or their English is proficient enough

for them to understand it, though not good enough for them to speak

it. The reasons why parents with language proficiency almost balanced

in both Chinese and English do not speak English to their English-speaking

children are the following: (1) most of their daily communication

is conducted in Chinese; (2) the communicative habit of using Chinese

formed through past years of communication with their children makes

them feel very uncomfortable in changing to the use of English; and

(3) it is easier for them to encode in Chinese though they decode

well in English. Such language-crossing communication is conducted

often between very intimate communicators. It could arouse embarrassment

or annoyance when it takes place between less intimate communicators.

Some people complained that some Chinese children spoke English to

them even though they insisted on speaking Chinese to the children.

However, these same people found that itwas natural when their own

children spoke English to them while they replied in Chinese.

A kind of code-shifting phenomenon is found in Chinese family communication,

that results in a shifting in the above two patterns of family communication.

In intimate communication, the relationships of communicators are

well-developed and unmarked in communication, and the principal function

of communication is to transmit linguistic information. The first

language is the fastest and most accurate language to transmit linguistic

information. A speaker's first language can change during his/her

life. In a bilingual community where a mother tongue (L language)

is different from the language used in school and in most of other

societal domains (H language), the mother tongue is a child's first

language. However, when the child grows up and starts school, the

school language gradually becomes his/her first language, as it is

used most often and in most societal domains. This gradual change

of one's first language often results in a change in communicative

patterns of family communication. My observation shows that this change

occurs more frequently when children have studied in school for three

or four years. After three or fouryears' schooling, a child's ability

in English has become sufficient for daily communication and they

start to use it more than Chinese. This results in a shift in the

patterns of family communication. The former pattern with Chinese

as the main communicative medium for all the family members gives

way to a new pattern: children speak English (their first language)

to their parents who in turn speak Chinese (their first language)

to the children. This kind of language shiffing is possible when communication

takes place between intimates, such as family members, whose relationships

have been well-developed, and communication functions mainly to exchange

linguistic information. In this kind of linguistic-information-oriented

communication, communicators would use their first languages to exchange

messages in a more efficient way.

So far the parents we have looked at in the second case are either

almost balanced bilinguals or are good enough at understanding English.

In cases where their English language proficiency is not sufficient

for them to understand normal English communication, children have

to give up their own first language and accommodate their parents'

first language, Chinese. This phenomenon is found in almost all studied

families where parents are first-generation immigrants who speak little

English and where children are either born or raised in the United

States. If the children are proficient in their parents' first language,

communication can be conducted without much effort. If the children

are not proficient in the first language of their parents, communication

could be conducted in a difficult manner for both the children and

the parents. The former have to use a less proficient second language

to communicate, resulting in much delay and inaccuracy in both encoding

and decoding messages. The latter have difficulty too in decoding

the messages they are receiving and in getting across the messages

they are sending.

Cases are also found in which parents accommodate their children's

first language. This happens when the children are English-Chinese

bilinguals with low proficiency in Chinese. These children have acquired

English before they have had a good command of Chinese. In many cases

when communicating with their children, Chinese-English bilingual

parents find it very difficult to use Chinese to get across to their

children many things that the latter have never learned in Chinese.

In this case, the parents have to give up their first language, Chinese,

and accommodate their children's first language, English.

In sum, the patterns of code-selection in intimate communication are

generalized as follows: (1) When the first language of communicators

is identical, that language is readily used; (2) When the first languages

of communicators are not identical, each communicator may (a) use

his/her own first language or (b) accommodate the other's first language,

depending upon the language proficiency ofthe communicators. If the

communicators are almost balanced in both languages or their language

proficiency is sufficient for them to understand the second language,

type (a) happens. If a speaker is not an almost balanced bilingual

and his/her second language proficiency is not good enough for hinvber

to conduct normal communication, the other communicator(s) will accommodate

his/her first language.

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

The Chinese/English bilingual communication has demonstrated that

code-selection in bilingual communication is essentially based upon

relationships between communicators and their language proficiency.

The relationship between communicators is dynamic: it develops from

its initial defining stage through the intermediate developing stage

to its final developed stage. This dynamic nature of relationship

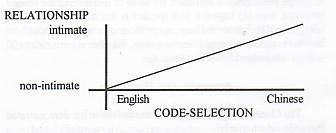

ascribes a dynamic nature of code-selection (Graph 2). In communication

between non-intimates, communicators know almost nothing about each

other, including ethnic backgrounds, language proficiency, etc., communication

is usually conducted in formal situations with an interethnic relationship,

and topics are most often non-intimate. Communication at this stage

is marked by its two fundamental functions: to transmit messages and

to establish relationships. At this stage, the majority or H language

is used, as it can best perform these two functions and mark an interethnic

relationship. As communication continues, communicators get to know

each other more and more, and their relationships develop from the

nonintimate stage to the semi-intimate stage. At this point, communication

is still marked by its two fundamental functions. At its early stage,

communication begins to involve some personal information, including

ethnic backgrounds, language proficiency, personal matters, etc.,

and the relationship gradually develops from an interethnic one into

an intraethnic one. To develop amore intimate intraethnic, socially

equal and informal relationship, communicators use a native language

more often in communication. As communicators enter the final stage

of relational development that is, the stage of the intimate relationship,

relationships between cominunicators have been well developed and

communication functions primarily to transmit messages. To transmit

messages in a more efficient way, communicators, depending upon their

language proficiency, will select a code that is better for encoding

and decoding messages.

Graph 2. Relationships and Code-Selection in Chinese Americans' Bilingual

Communication.

Language proficiency will

make some adjustments to the above general modes ofcode-selection.

Lower language proficiency will limit the selection of the codes specified

in the above modes. Kinds of communities, native communities ornon-native

communities, situations, formal or informal, and involvements ofdifferent

relationships will also modify the above general modes of code-selection.

NOTES

1. It is disputed whether all these local speeches are dialects or

languages. I use "dialect" as it is traditionally used by

Chinese from political, historical, and linguistic points of view.

REFERENCES

Auer, J. C. P. 1984. Bilingual conversation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

--- 1988. A conversational analytic approach to code-switching and

transfer. In M. Heller, ed., Codeswitching: anthropological and sociolinguistic

perspectives Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 187-214.

Bentahila, A. 1983. Motivations for code-switching among Arabic-French

bilinguals in Morocco. Language and Communication, 3: 233-243.

Blom, J-P. and Gumperz, J. J. 1972. Social meaning in linguistic structures:

codeswitching in Norway. In J. J. Gumperz and D. Hymes, eds., Directions

in sociolinguistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. 407-34

Brown, P., and Fraser, C. 1979. Speech as a marker of situation. In

K R. Scherer and H. Giles, eds., Social markers in speech. Cambridge:

Cambridge UP. 33-108.

Byrne, D. 1969. Attitudes and Attraction. Advances in Experimental

Social Psycholo~y,4,35-89.

Ervin-Tripp, S. M. 1964. An analysis of the interaction of language,

topic, and listener. American Anthropologist 66, 86-102.

Ferguson, C. A. 1959. Diglossia. Word, 15,325-40. AlsoinP.P. Gigholied.

1972. Language and social context. Harmondsworth: Penguin. 232-5 1.

Ferguson, C. A. and Heath, S. B., eds. 198 1. Language in the USA.

Cambridge: CambridgeUP.

Fisher, B. A. andEllis, D. G. 1990. Smallgroup decision making: Communication

and the group process. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

Fishman, J. A. 1966. Language loyalty in the United States. The Hague:

Mouton.

---- 1967 Bilingualism with and without diglossia: diglossia with

and without bilingualism. Journal ofSocial Issues 23, 29-38.

---- 1972. Societal bilingualism: stable and transitional. The Sociology

of Language 4,91-106.

Fishman, J., Cooper, R. L. and Ma, R. 1971. Bilingualism in the Barrio.

Bloomington: Indiana UP.

Flores, N. and Hooper, R. 1975. Mexican Americans' evaluation of spoken

Spanish and English. Speech Monographs 42, 91-8.

Genesee, R., and Bourhis, R. 198 1. Language variation in social interaction:

the importance of situational and interactional context. Unpublished

manuscript, Department of Psychology, McGill University.

Giles, H. 1979. Ethnicity markers in speech. In K.R. Scherer and H.

Giles, eds., Social markers in speech. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. 251-290.

Greenfield, L. 1970. Situational measures of normative language views.

Anthropos 65,602-18.

Gumperz, J. J. 1982. Discourse strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Haugen, E. 1953. The Norwegian language in American: a study in bilingual

behavior. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P.

Heller, M., ed. 1988. Codeswitching: Anthropological and Sociolinguistic

Perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lambert, W. E. 1967. The social psychology of bilingualism. Journal

of Social Issues, 23,91-109.

Lance, D. 1975. Spanish/English code-switching. In C. E. Hernandez-Chaves

and A. Beltramo, eds., El lenguaje de los Chicanos. Arlington, VA:

Center for Applied Linguistics. 138-53.

McClure, E. 1977. Aspects of code-switching in the discourse of bilingual

Mexican-American children. In M. Saville-Troike, ed, Linguistics and

anthropology. GURT. Washington, DC: Georgetown UP.

Pfaff, C. 1976. Functional and structural constraints on syntactic

variation in code-switching. In S. B. Steever, C. A. Walker and S.

S. Mufwene, eds., Papers from the parasession on diachronic syntax.

Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society. 248-59.

Poplack,S. 1980. Sometimes I'll start a sentence inEnglishytermino

enespanol: Toward a typology of code-switching. Linguistics, 18, 361-79.

Ryan, E. and Giles, H., eds. 1982. Attitudes towards language variation:

social and applied contexts. London: Edward Arnold.

Sankoff, D., and Poplack, S. 1981. A formal grammar for code-switching.

Papers in Linguistics 14, 3-46.

Scotten, C. M. 1983. Negotiation of identities in conversation: A

theory of markedness and code choice. International Journal of Sociology

of Language 44,115-35.

1988. Code switching as indexical of social negotiations. In Heller,

ed, Codeswitching: Anthropological and sociolinguistic perspectives.

Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 151-86.

Scotten, C. M., and Ury, W. 1977. Bilingual strategies: the social

flinctions of code-switching. Linguistics 193, 5-20.

Valdds-Fallis,G. 1981. Codeswitchingasdeliberateverbal strategy: amicroanalysis

of direct and indirect requests among bilingual Chicano speakers.

In R. P. Duran, ed, Latino language andCommunicative behavior. Norwood,

NJ: ABIEX

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J., and Jackson, D. 1967. Pragmatics of human

communication. New York: WW Norton and Company.

Weinreich,U. 1968. Languages in contact: Findings and problems. The

Hague: Mouton.

Woolford, E. 1983. Bilingual code-switching and syntactic theory.

Linguistic Inquiry, 14 520-36.

Xia, N. 1992. Maintenance of the Chinese language in the United States.

Bilingual Review, 17 (3):195-209.

Zentella, A. C. 198 1. Hablamos los dos. we speak both: Growing up

bilingual in El Barrio. PhD thesis: University of Pennsylvania.

- End -

About

the author: (Published in

Language Quarterly Vol. 31:304: 177-195)

Contact the author

Email your comments to chinatown-online.com

|